Changing Currents Feature No. 3

Posted: November 4, 2014

Henry Pattison: The Tale of an Immigrant Shanty-Boy

Our new exhibit Changing Currents: Reinventing the Chippewa Valley is now open for preview. Each month leading up to the official grand opening celebration on December 7, we will preview one aspect of the history explored in each of the exhibit's six sections. Each article will introduce a different era of Chippewa Valley history, digging deeper into the story of a particular event, person, or theme. The section we call "People Are Flooding In" explores the explosion of population in the Chippewa Valley after the Civil War as waves of migrants from New England, Canada, and Northern Europe streamed in, and follows their lives through the rise and decline of the lumber industry.

One Sunday afternoon in September 1935, a travel writer for the Wisconsin State Journal in Madison found himself a guest at a family reunion picnic on a large 640-acre farm near Durand. The host was Thomas J. Pattison, a member of the state highway commission who otherwise resided in Madison. Thomas's brothers held occupations of equally high esteem: one a judge in Alma, another a lawyer and hotel owner in Durand, a third a merchant in Minneapolis, and a fourth a local farmer and auctioneer. His college-educated sister had also returned for the reunion, leaving behind her husband who worked in construction finance in Berkeley, California. The patriarch of this notable family, 81-year-old Henry Pattison, "still living in robust health," was there too. Impressed by such a "stalwart" group, the writer proclaimed, "here indeed was one of the families with which we typify America in our political boastings to lesser breeds of foreign lands."

Henry Pattison and sons, early 1910s.

Back row: Francis, John, "Judge" Lee, Abe; front row: Edward (E. S.), Henry, Thomas J.

All of Henry's sons but John lived long, prosperous lives. John became a firefighter in Chicago, but he died at age 34 of injuries he suffered several years earlier in a fire at the Chicago Union stockyards. Courtesy MaryAnn Pattison.

The Pattisons were by any standard immensely successful. Even in the midst of the Great Depression, Henry Pattison's surviving sons and daughter maintained both their businesses and social standing. However, the travel writer's glowing description of the Pattisons obscures the difficult beginnings of the family's prosperity. Henry Pattison was, after all, born to a tenant farmer in Ireland. At the time they immigrated, many Americans would have considered Catholic Irish people like Henry and his parents to be prime examples of "lesser breeds of foreign lands."

Henry Pattison's rags-to-riches story is fascinating in itself, but by taking a closer look at the key years in Henry's life, we can also come to understand life in the Chippewa Valley during the 1860s and 1870s. What was it like to work in the lumber industry during the boom years? What other opportunities were available? How important were family relationships to the immigration and settlement of the Chippewa Valley and to the fortunes of young individuals? Henry was above average in aptitude and achievement--most immigrants did not attain his level of wealth and status--but he nonetheless proves a fine example because his life to a great extent mirrored the broader history of the region.

Thanks to the in-depth research of family historian MaryAnn Pattison, we know an incredible amount about the life of Henry Pattison. Most of the details that flesh out this story derive from her commitment to digging up obscure sources and interviewing old relatives. MaryAnn is herself now 90 years old.

Arrival

In 1854, Wisconsin's Ojibwe signed their last treaty with the U.S. government and finally acquired reservations on their homelands. That year, the tiny village which later became the city of Eau Claire contained fewer than 100 souls and still went by the English name Clear Water. Miles Durand Prindle still lived in New England. It would be another two years before he came to Chippewa Valley to found the city that bears his middle name.

In February 1854, thousands of miles away on a small tenant farm in County Queens in central Ireland, Henry Abraham Pattison was born. Life and family circumstances beyond young Henry's control would soon carry him from the Emerald Isle and into the diverse and rapidly expanding communities of the lower Chippewa Valley.

In 1861, seven-year-old Henry accompanied his parents Abraham and Anna Pattison on a journey across the Atlantic Ocean. They left behind Henry's infant sister Anna in the care of family and friends. Like many immigrant families who eventually settled in the Chippewa Valley in the late 19th century, the Pattisons first made their home in a different part of the U.S. before continuing to our area. Also like many immigrants, they were following family members who had already come to the United States.

Henry Pattison's mother Anna (maiden name Worrell) had relatives who had settled in southern Wisconsin. In 1855, a year after Henry was born, his uncles Thomas and William Worrell and his aunt Catherine Worrell came to America. The famous Irish potato famine had ended a few years earlier, but the eviction of tenant farmers and persecution of Catholics continued. Both the Worrells and Pattisons were Catholic. After spending a year in Rahway, New Jersey, some of these Worrell relatives settled in Madison, Wisconsin, and others on farms in the nearby township of Fitchburg. The year was 1856. When Henry's parents brought him to the United States five years later, they joined Anna's relatives in Madison.

The Pattisons arrived in the city only a few weeks after the Battle of Fort Sumter had ignited the American Civil War. Henry's father Abraham was a farmer by trade, but he had also served ten years in the English military. Abraham wanted to enlist to fight for the Union, but Anna refused to let him leave for yet more military service. According to Henry's recollection, Abraham nonetheless made his way to Camp Randall, where he used his army experience to train new recruits. It is quite possible that at Camp Randall "Abe" Pattison met "Old Abe" the bald eagle, the famous Chippewa Valley bird that became the inspirational mascot of Wisconsin's 8th Infantry Regiment.

From age seven to thirteen, Henry lived in Madison, probably in the city's predominantly Irish Fourth Ward. One historian described the Fourth Ward as "a rough-and-tumble immigrant neighborhood located southwest of the Capitol where railroad workers and their new families began to integrate into society, often employed as laborers, liverymen, and seamstresses."[1] Indeed, in Madison Henry's father Abraham worked for one of the railroad companies that were rapidly crisscrossing the state with new lines. Young Henry probably also spent time with his relatives in Fitchburg, a community made up predominantly of Irish farmers. At 76 families, Fitchburg's Irish formed the largest congregation of a single ethnic group in southern Dane County.

Men and women with similar ethnic, religious, and linguistic backgrounds often gathered together, buying farmland near one another or occupying particular neighborhoods in towns and cities. This pattern of settlement occurred in other parts of Wisconsin, too. Frenchtown in Chippewa Falls and several clusters of Norwegian farms in western Chippewa County are examples from the Chippewa Valley.

Some of the Fitchburg Irish, including Henry Pattison's Worrell uncles, left Dane County in the mid 1860s in order to purchase land farther north. In the "Big Woods" between the new towns of Durand and Mondovi in Pepin and Buffalo Counties, a very different pattern of settlement took place. People of various ethnic backgrounds ended up scattered almost randomly across the land. For example, the 1870 census showed that Canton Town in Buffalo County, where Thomas Worrell acquired land, contained adults who had been born in the following places: Ireland, Scotland, England, France, Norway, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Canada, and many German states--Prussia, Hesse, Baden, Mecklenburg, Saxony, and Austria--as well as nearly every northern state in the Union and even a few southern ones: Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee. It truly was a grand mixing of people.

Growing Up Fast

Henry's life changed dramatically in 1867. That year, his father Abraham died of injuries received in a rail switching accident. Abraham's death left Anna with two sons to care for, thirteen-year-old Henry and two-year-old John, the latter who had been born in Madison. For temporary support, she and the children moved north to stay with her Worrell brothers in Buffalo and Pepin counties. (Laura Ingalls Wilder was born the same year on a farm in another part of Pepin County.) There, in 1868, Anna remarried an English immigrant named John Stringer, who was recently widowed and had eleven children of his own.

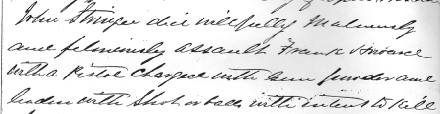

Henry's new stepfather John Stringer had been one of the first permanent white settlers in the Bear Creek Valley east of Durand, having arrived with his family in 1862. Both family stories and court records show Stringer to have been a mean-spirited man, perhaps even an all-around bully. His name appears in Pepin County court records more than twenty times for such crimes as stealing cattle, stealing oats, trespassing and damaging private property, and frequently failing to pay people for various services they rendered him. At his worst, according to an 1875 charge in the state Circuit Court, "John Stringer did willfully, maliciously, and feloniously assault Frank Howard with a pistol charged with gun powder and laden with shot or balls with intent to kill."[2] At one point, even his own lawyer sued him! One family story relates that Stringer kicked Henry Pattison and his younger brother out of the house because it was already full with Stringer's own eleven children. Another says Henry fled with his little brother as soon as he could to escape his stepfather's brutality.

Above are the key lines in an October 1875 indictment of John Stringer. Unfortunately, the case file does not contain a judgment, so we do not know how the case was resolved. Within a few months he was back in court as both plaintiff and defendant in new cases, so he evidently was not imprisoned. In an interesting side note, the twelve-man jury that forced Stringer to pay a large mortgage debt in 1873 included Charles Ingalls, father of then six-year-old Laura Ingalls (later Wilder).

In any event, 14-year-old Henry was on his own. He first "worked out" or "farmed out," working as a farmhand for other families. To "work out" meant to work for people other than one's immediate family in order to earn a wage and/or room and board. It was a relatively common practice in farm communities and small towns, especially for unmarried young people. Young men like Henry usually became farmhands, while young women often worked as maids or domestic help for wealthier families.

As a farmhand in Pepin and Buffalo counties in the late 1860s, Henry helped clear the "Big Woods" in order to bring more Chippewa Valley land under cultivation. The earliest work Henry got as a farmhand was growing, cutting, threshing, and selling the first 200 bushels of wheat harvested on the farm of James Hubert Fox, another Irish immigrant who had come to the Chippewa Valley with his family by way of Dane County. Henry later recalled in a newspaper interview that the man who purchased half of his very first harvest "literally speaking skipped and never paid for the wheat."

In the Pines

In 1871, when he was a few years older and strong enough for the work, Henry Pattison took up the seasonal life of a "shanty-boy" (what would later be called a lumberjack). Hired by the Eau Claire Lumber Company, he left the basswood, oak, and maple of the "Big Woods" for the pine forests farther up the Chippewa Valley. Henry worked for the Eau Claire Lumber Company when the company was quickly expanding its operations. It had been founded in 1866 with Joseph G. Thorp as president, and grew rapidly at a time when other lumber companies were struggling through a mild economic depression. The company's land holdings were east along the Eau Claire River and its tributaries rather than farther north along the Chippewa River, but they contained some of the best stands of white pine in the state. This helped Thorp's company grow to include numerous sawmills, a flourmill, and even a general store by the mid 1870s.

How did Henry contribute to this growth? Each winter he and other men moved to logging camps on the company's land. Rising before dawn, they spent the cold winter days chopping and sawing whole stands of white pine before returning to their crowded bunkhouses after dark. Each spring Henry participated the annual log drives down the river, helping to raft and sort the logs as they made their way to holding ponds at Eau Claire or beyond. During summer and fall he worked, probably as a simple laborer, in the company's shingle or sawmill in the tiny village of Meridean, a town which was originally located on an island in the Chippewa River about 15 miles below Eau Claire. Some of the lumber Henry helped produce was used in the construction of towns like Eau Claire and Durand, but most was rafted much farther downriver, where it enabled settlement in areas with fewer usable trees-places like Iowa, Missouri, and Nebraska.

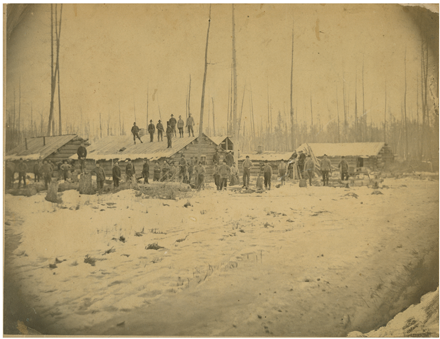

The earliest confirmed photographs of logging camps in the Chippewa Valley date to 1879-80, and were taken of Eau Claire Lumber Company operations along the Eau Claire River and its tributaries. Henry Pattison worked in the same areas only a few years earlier. All five photographs from CVM collections.

1) Eau Claire Lumber Company logging camp near Hay Creek, a tributary of the Eau Claire River, winter 1879-80.

2) Eau Claire Lumber Company logging camp, North Fork of the Eau Claire River, winter 1879-80.

3) Probably Eau Claire Lumber Company logging camp at Altoona, 1880s.

4) Eau Claire Lumber Company steam-powered mill at Eau Claire, about 600 feet from the Dewey Street Bridge, 1872. Henry Pattison could very well be one of the men in this photograph.

5) Eau Claire Lumber Company rafts at the confluence of the Eau Claire and Chippewa Rivers, ca. 1878.

The whole lumber industry was booming in the early 1870s in the Chippewa Valley. Production in Eau Claire reached its first peak in 1874 at more than 170 million board feet. There was plenty of work for young men like Henry.

However, lumber work was dangerous, each season in its own ways. Falling trees were always a hazard in the lumber camps. Frostbite competed with saw and axe blades taking men's fingers and toes in the winter. Besides the threat of drowning or being crushed by logs if a man fell into the river on a log drive, people occasionally fell victim to the charges of gunpowder--and later dynamite--that were used to break up logjams.

Millwork too could be life threatening. Henry Pattison was lucky to survive the summer of 1871 in the Meridean mills. According to the 1925 History of Dunn County, Wisconsin, "On Sept. 30, 1871, the boiler in the shingle mill [at Meridean] exploded, whereby Nora Nebow, a young girl of 16, and her uncle, Peter Aas, employed as a fireman, where killed." Between 1863 and 1880, the same shingle mill "had been destroyed three times by fire and rebuilt."[3]

One summer Henry escaped the dangers of millwork by carrying mail. Jerome B. Garland, a partner in Eau Claire Lumber Company and manager of the Meridean mills, also worked as the village's postmaster in the early 1870s. Henry, likely employed by Garland, spent three months driving a stagecoach route between Eau Claire and Meridean. He was the first person to carry mail between the two towns. At the time, driving the stage route was probably just a way for Henry to earn a little extra money before he headed back to the logging camps, but decades later he would return to the post office; in 1915, Senator Paul O. Husting would recommend Henry to President Woodrow Wilson, who named him postmaster of Durand the following year. Henry would hold that position for eleven years.

Charles G. Branch delivers mail on the new Rural Free Delivery route #2 out of Durand, ca. 1903. Branch still worked this route when Henry Pattison became postmaster in Durand in 1916. Rural routes did not exist when Henry himself carried mail between the towns of Eau Claire and Meridean one summer in the early 1870s, but he too used a horse-drawn coach. From CVM collections.

If making a living as a shanty-boy weren't difficult enough for young Henry, in 1872 his mother Anna died at the Stringer home in Pepin County due to complications of childbirth. She was only in her mid-thirties, and it left Henry, himself only 18 years old, without either of his parents. Life was hard, work in the lumber industry was grueling, and Henry was eager to start fresh.

A New Life

When staying in cities like Eau Claire or small towns like Meridean, lumber workers often stayed in boarding houses. If available, they usually chose the one run by women of the same ethnicity. A Pattison family story explains that Henry Pattison's future wife Catherine "Kate" Sweeney owned a boarding house in Eau Claire, and that is where the couple met. Whether it is true or not, their families had previously been acquainted. Kate Sweeney came from the same Irish farm community in Fitchburg where Henry's uncle William Worrell once lived, and some of Kate's own relatives had settled near Durand in the 1860s. When Henry and Kate married in 1876, the wedding took place at St. Mary's Catholic Church in Oak Hall, now a neighborhood of Fitchburg.

By 1876, Henry had something more to offer his prospective wife than merely his companionship. The year before, he had cajoled his uncle William Worrell to help him acquire farmland. William and his wife Mary purchased 80 acres along Bear Creek near the border of Pepin and Buffalo counties. The Worrells retained legal title to the land for several years, but they let Henry run the farm (and pay the property taxes!).

The seller in this deal was none other than Henry's stepfather John Stringer, who may have been selling the land to pay legal debts. It turns out Stringer wasn't inherently bad after all. In addition to helping Henry acquire this land, Stringer coordinated the construction of a 16 x 30 foot log cabin right next to the creek, using wood provided by a friendly neighbor. One family member recalled the cabin: "Three rooms made up the ground floor, a living room and a bedroom, with the kitchen being in the lean to and in here was the only heat in the house. The upstairs part was divided by curtains into bedrooms." Initially, the only other building on the property was a horse shed.

Pattison log house, drawn by Karen Helland Pattison based on the descriptions of people who grew up in the house. Courtesy MaryAnn Pattison.

Standing, left to right: John, Edward, Thomas, Margaret, Abe

Seated: Anna, George Leo, Henry, Francis, and Kate (Sweeney) Pattison

Photographed ca. 1894 by Thomas G. Raitt, who worked as a professional photographer in Durand from about 1891 to 1912. Courtesy MaryAnn Pattison.

Henry and Kate Pattison moved into the little cabin on Bear Creek after their wedding and immediately got to work building a farm and a family. All eight of their children were born in that cabin.

Henry and Kate's farm became the basis of their later wealth. As their children grew, so did the farm. At first they grew mostly wheat and oats, but Henry soon joined in the regional transition to dairy farming. From the handful of Jersey milk cows he owned in the 1870s, the Pattison farm grew over the next forty years into a 560-acre show farm featuring a large herd of registered Jerseys, massive dapple-grey Percheron draft horses, and Shropshire sheep. After twenty-one years in the log house, in 1897 the Pattisons finally built a large farmhouse they could be proud of. Around that time, they branded the estate Emerald Stock Farm in honor of their Irish heritage.

The rest of Henry's life is equally fascinating, but it is his key years in the 1860s and 1870s that tell us so much about the opportunities that attracted thousands of families like his from Northern Europe, New England, and Canada to the Chippewa Valley. We often focus so heavily on the lumber industry that we overlook other reasons people came. For some men, working in the woods was a lifelong career choice based on skills and personality. For Henry and many other men, laboring in the lumber industry was a way of earning startup cash in order to pursue other opportunities. Some started businesses in town. Others, like Henry, wanted to own and work the land. The "Big Woods" region of the lower Chippewa Valley contained excellent land, suitable for either grain- or dairy-based agriculture, and it filled with farmers during the same years logging took off farther north.

Finally, it is always worth noting just how important an individual's relationships with family and community are to personal success. Henry Pattison was without question a high achiever, but his life would have turned out very differently without the help of his uncles and their acquaintances from the Irish-American community that first coalesced in Fitchburg.

You can learn more about immigration, the Euro-American settlement of the Chippewa Valley, and work in the lumber industry in CVM's new exhibit Changing Currents: Reinventing the Chippewa Valley. If you're a city dweller interested in the life of farmers like Henry Pattison, our visitor-favorite exhibit Farm Life is also a must-see.

[1] Thomas P. Kinney, Irish Settlers of Fitchburg, Wisconsin, 1840-1860 (1993), 12.

[2] Circuit Court Case Files, 1858-1946, Pepin Series 18, box 7, "53 State of Wisconsin vs. Stringer, John 1875." University of Stout Archives, Area Research Center, Menomonie, Wisconsin.

[3] F. Curtis-Wedge, Ph. D., Geo. O. Jones and others, comp. History of Dunn County, Wisconsin, (Minneapolis-Winona, Minnesota: H. C. Cooper, Jr. & Co., 1925), 216.

Send this blog post to someone:

SUBMIT