Changing Currents Feature No. 4

Posted: November 6, 2014

At Risk of Being German

The grand opening of our new exhibit Changing Currents: Reinventing the Chippewa Valley is rapidly approaching. Leading up to the official grand opening celebration on December 7, we will continue to highlight individual stories from each of the exhibit's six sections with special in-depth features. Each article will introduce a different era of Chippewa Valley history, digging deeper into the story of a particular event, person, or theme. The section we call "Making Americans" explores the variety of definitions people used to understand what it meant to be an "Ameircan" during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

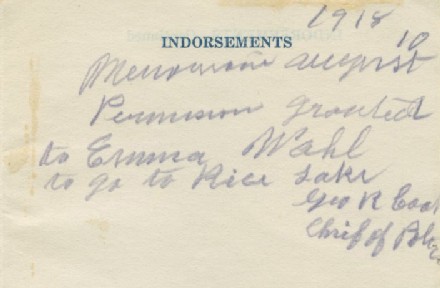

One Saturday in August 1918, long-time Dunn County resident Emma Wahl found reason to visit to Rice Lake. Before she could depart, however, she had to stop by the local police station in Menomonie. There, Chief of Police George R. Cook was required to give his permission for her to leave the city. What had Emma done to earn such scrutiny? She wasn't a felon. She wasn't a criminal of any kind. She was, like many residents of the Chippewa Valley, an ethnic German.

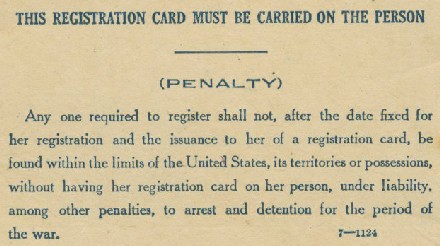

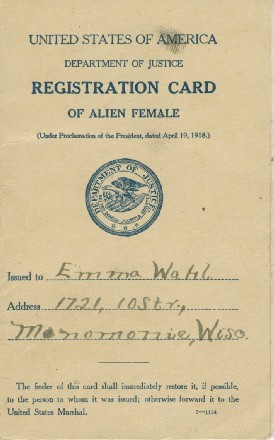

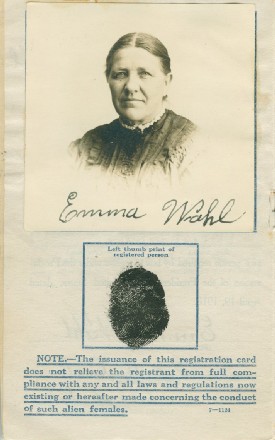

A month earlier, Emma had been forced to register with the government as an "alien female." The registration card she was given contained her signature and a photograph for identification. It also contained a serious threat:

In the midst of World War I, many Americans came to fear that German-Americans would sympathize with their homeland and weaken the American war effort, or worse, that German immigrants were in fact enemy spies. Following an executive order by President Woodrow Wilson on April 19, 1918, Emma Wahl and thousands of other German-American women were required at all times to carry a registration card identifying each of them as a potential threat to national security.

Under Pressure

German-American men like Emma's husband Ernst (or Ernest) had been subject to the same restrictions following an executive order five months earlier. It didn't matter that Ernest Wahl had been in America for over 50 years since arriving with his parents as a teenager in 1864. Or that he had filed naturalization papers in 1880. He had never completed the naturalization process and therefore remained an "alien."

As anti-German sentiments mounted and alien restrictions were put in place, Ernest Wahl finally felt pressured to complete his naturalization. But he was too late. On April 18, 1918, the day before President Wilson declared that German-American women like Emma would be subject to alien registration, Ernest saw his second attempt to become a naturalized American citizen fail. The court rejected his petition for citizenship on the grounds that he had waited too long to finish the process.

The United States Supreme Court had recently decided a case affirming that old declarations of intention like Ernest's were accountable to the Naturalization Act passed by Congress in 1906. The Naturalization Act stipulated that foreign-language aliens were required to complete naturalization--to petition for citizenship--within seven years after declaring their intention to do so. In early January 1918, as Ernest and Emma contemplated what the new alien registration meant for Ernest, the case United States v. Morena stated that old declarations like Ernest's had been grandfathered in under the Naturalization Act, but that the seven-year limit then applied from the date of the Act's passage (that is, 1906). In 1918, Ernest was still five years too late. Ernest's failure to become naturalized affected more than just his own freedom.

Various pages and excerpts of Emma Wahl's registration card are shown throughout this article. The original registration card is part of CVM's collections.

Who Is a Citizen?

The most astonishing aspect of this entire story is that Emma Wahl, a sixty-one-year-old mother of nine, had been born right here in Dunn County, Wisconsin. She was a native-born citizen of the United States. In a situation that seems surprising today, Emma's American citizenship, acquired at birth, was suspended on April 2, 1877, the day she married Ernest. "Any American woman who marries a foreigner takes the nationality of her husband," proclaimed a document from the U.S. Attorney General clarifying the President's 1918 order on the Registration of German Alien Females.

So long as Ernest had not become a naturalized citizen, the United States considered both he and Emma citizens of the German Empire. Although she was born and raised in the United States and had never set foot in the German Empire, Emma was deemed a potential threat and became subject to severe government restrictions on "alien" citizens simply because she had married a German-American man forty years prior.

Whether a foreign woman had married before immigrating or an American native had married a foreign citizen in the U.S., she was not in most cases considered eligible for her own naturalization. Emma Wahl could not have "re-naturalized" on her own accord. Her naturalization status depended entirely on Ernest so long as he was alive. So, in the end, Emma and Ernest Wahl became two of some 250,000 German-Americans who registered as German aliens with the U.S. government during World War I.

Legal Conundrums

Even if Emma Wahl had been a U.S. citizen in 1918, she could not have voted. American women were still fighting for that right. Indeed, the women's suffrage movement arguably peaked just as the United States entered World War I. Several prominent American women camped out in permanent protest outside the White House in 1917. President Wilson's "war for democracy" in Europe was a farce, they concluded, if at the same time twenty million American women were denied the right to vote. Under such pressure, Wilson publicly changed his position and in 1918 began to openly advocate giving women the right to vote. The Nineteenth Amendment passed in Congress and was ratified in 1920.

The Nineteenth Amendment in turn created problems administering immigration laws, even for men. Consider the following example. Say an immigrant man was fully eligible to become a citizen, but his wife could not speak English (which was-and still is-one of the requirements). Since a married woman's naturalization status derived from her husband, if the judge allowed the husband to become a citizen, the wife would then be able to vote, despite herself not possessing the required qualifications. In such cases, judges often denied men who were otherwise fully qualified to become American citizens. (If you find it hard to follow all of these legal explanations, imagine how you'd feel if your citizenship depended on understanding them!)

The remedy came in 1922, when Congress passed the Married Women's Act. Also known as the Cable Act, it finally granted women independence in terms of naturalization. Beginning in 1922, American-born women who married foreigners retained the American citizenship of their birth, while foreign-born women could no longer acquire U.S. citizenship simply by marrying an American man. There was, however, one glaring exception in the Cable Act: since Asian men were barred entirely from becoming U.S. citizens, any American woman who married an Asian man still forfeited her own citizenship.

Despite these changes, there is no evidence that either Ernest or Emma Wahl ever became naturalized citizens. Perhaps they were bitter at the treatment they received from the American government and local citizens during World War I and saw maintaining foreign citizenship as a political statement. Or perhaps once the anti-German fever abated after the war, they saw no reason to go through the hassle yet again.

Complicated Lives

We often study separately things like World War I, immigration, and the fight for women's rights, digesting one theme at a time. The situation of Emma and Ernest Wahl is a reminder that the people who lived through these changes experienced them in relation to one another and all at the same time. For Emma Wahl, wartime legal limitations based on birthplace and national identity overlapped with other categories in which legal rights differed--gender and marital status.

Other anti-German laws passed during World War I restricted speaking and writing in German. These laws, which targeted German-language schools and newspapers, also affected many Chippewa Valley residents, perhaps including Emma's children or grandchildren.

See Emma Wahl's registration card up close--and learn about the plight of a Chippewa Valley newspaper editor who ran afoul of anti-German laws--in CVM's new exhibit Changing Currents: Reinventing the Chippewa Valley. Join us for special grand opening events Sunday, December 7, from 1 to 5pm.

Send this blog post to someone:

SUBMIT